March 5, 2023 – future Public Safety Training Facility – Atlanta

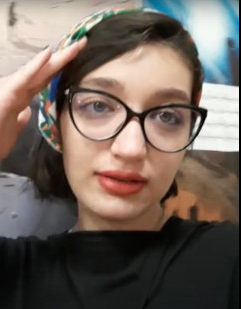

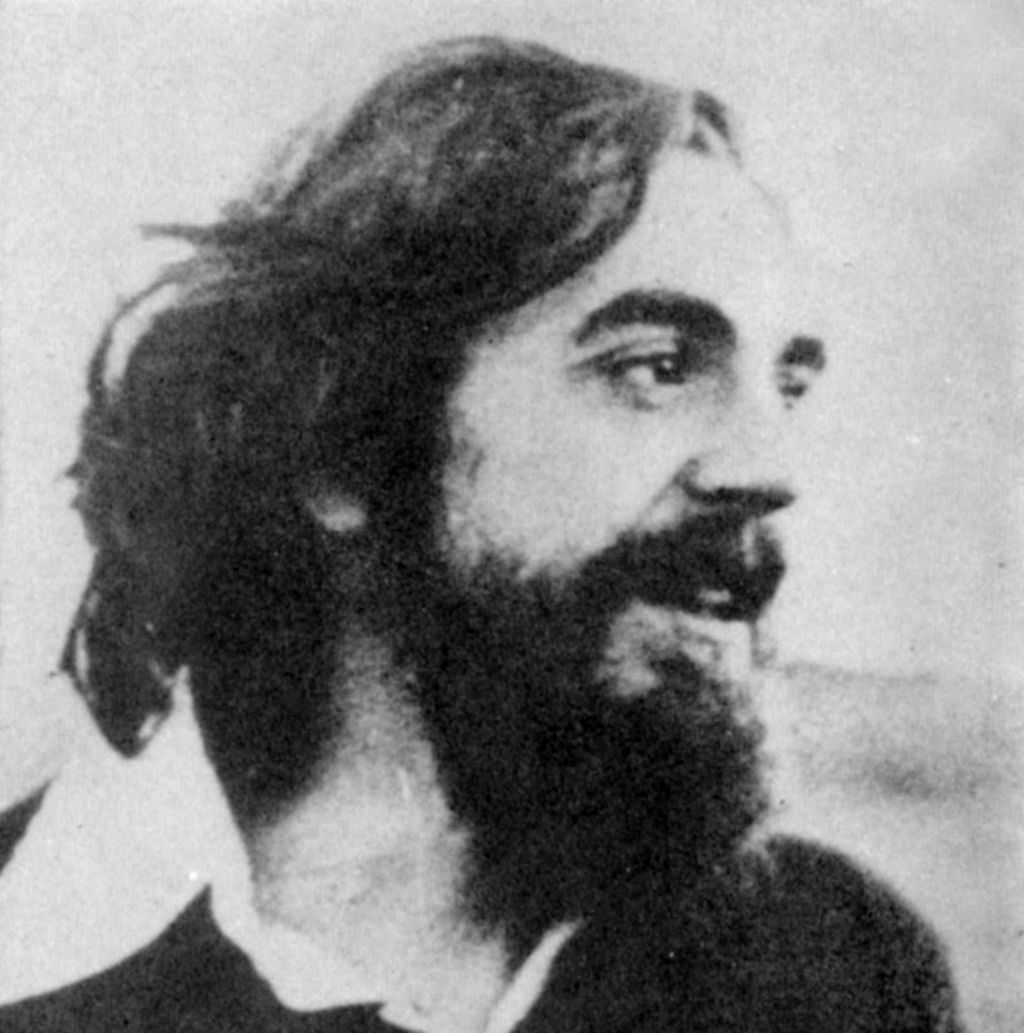

19-year-old. Arrested and charged with a count of domestic terrorism, aiding and abetting arson: pending trial

- Last update: 15:12 - First published

Fighting against Cop City

Massachusetts resident Ayla King is accused of storming the DeKalb County construction site of Atlanta Public Safety Training Center in March 2023 with more than 20 other masked activists after a nearby protest concert. Ayla, who faces a sentence of five to 20 years in prison, requested an accelerated trial in late 2023, shortly after their indictment, alongside 60 others charged with domestic terrorism, racketeering, money laundering and other charges (RICO Act). The proceedings dragged on due to a procedural debate over whether the trial began on time. Supporters and defenders of freedom of expression are denouncing the charges, as well as new state laws toughening penalties for people committing “acts of vandalism” during demonstrations.

During the movement to stop Cop City, police randomly arrested Ayla for attending a music festival in Weelaunee Forest alongside several hundred other people. The police were lashing out in response to the act of sabotage that had taken place nearly a mile away at the same time as the festival. Like the other 22 people they randomly arrested at the music festival, the police charged Ayla with domestic terrorism.

According to eyewitness reports, the police detained more people, but they focused on arresting the ones who did not provide home addresses in Atlanta. They presumably did so in order to cherry-pick evidence bearing out the narrative about “outside agitators” that racist police and politicians in the South have employed at least since Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. described this strategy in his “Letter from Birmingham Jail.”

A few months later, along with 60 others, Ayla was additionally charged with violating the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (RICO) Act. At 19 years of age, Ayla bravely filed for speedy trial. Yet it has taken more than two years for the case to come to trial, presumably because the prosecutors have so little to work with.

Version of the Police

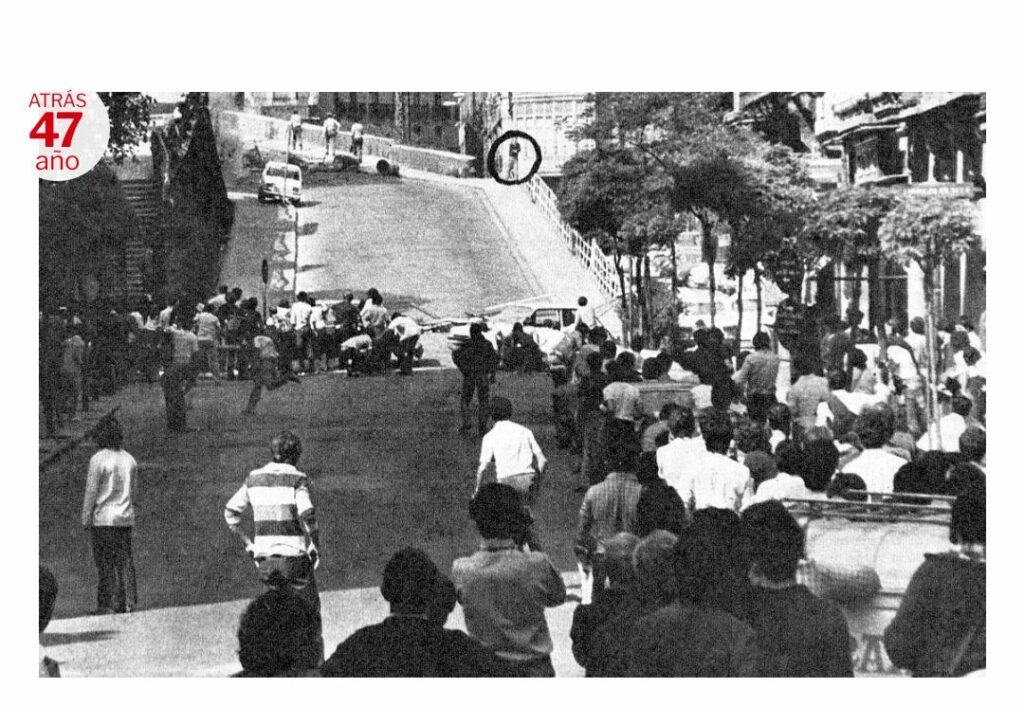

Officials say around 5:30 p.m. Sunday, dozens of protesters left the nearby South River Music Festival, changed into black clothing, and entered the site of the controversial proposed police training center.

“This was a very violent attack that occurred, this evening very violent attack,” Atlanta Police Chief Darin Schierbaum said near the scene. He called the incident a “coordinated, criminal attack against officers.” “Actions such as this will not be tolerated. When you attack law enforcement officers, when you damage equipment – you are breaking the law,” .

After receiving backup from numerous agencies, Atlanta police fanned out into the woods and detained at least 35 people. Monday, police say they charged 23 of those detained with a count of domestic terrorism.

Late Sunday evening, Atlanta Police released the following statement:

On March 5, 2023, a group of violent agitators used the cover of a peaceful protest of the proposed Atlanta Public Safety Training Center to conduct a coordinated attack on construction equipment and police officers. They changed into black clothing and entered the construction area and began to throw large rocks, bricks, Molotov cocktails, and fireworks at police officers.

The agitators destroyed multiple pieces of construction equipment by fire and vandalism. Multiple law enforcement agencies deployed to the area and detained several people committing illegal activity. 35 agitators have been detained so far.

The illegal actions of the agitators could have resulted in bodily harm. Officers exercised restraint and used non-lethal enforcement to conduct arrests.

With protests planned for the coming days, the Atlanta Police Department, in collaboration with law enforcement partners, have a multi-layered strategy that includes reaction and arrest.

The Atlanta Police Department asks for this week’s protests to remain peaceful.

No officers were injured in the confrontation. A handful of protestors were treated for minor injuries when officers say they used “non-lethal” force against the group.

The version of the Justice (?)

Judge Kevin Farmer declared a mistrial in Ayla’s RICO case today, as some 80 supporters gathered in the courtroom and rallied outside. The mistrial comes in the wake of two years of delays to Ayla’s case being heard. When charged with RICO in 2023 after being arrested at a Stop Cop City music festival, Ayla was quick to demand a speedy trial and in 2023 a jury was selected under the judge previously presiding over the case, Judge Adams. The jury never even heard opening arguments, as the case was sent to appeals. The court of appeals refused to dismiss Ayala’s charges, but determined that the court proceedings must be public to media (as Judge Adams had refused to allow news media and livestreaming of the court while Ayala’s initial jury was selected).

Due to these procedural issues, Judge Farmer ruled the case a mistrial. In ostensibly protecting one “right,” the right to public court proceedings, Fulton County continues to completely disregard Ayala’s right to a speedy trial. Those familiar with Fulton County, where criminal charges typically take several years to resolve, will find no surprise here. Following the continued, persistent violation of Ayla’s rights, Ayla’s lawyer is appealing the mistrial. This leaves Ayla’s case in limbo. Currently, it is expected that, paradoxically, Ayala’s “speedy trial” will be delayed to September or October, while the trials for other defendants in the RICO case may begin this summer.

Ayla’s case exemplifies the miscarriage of justice in this politically-motivated prosecution. Cases like these are “process as punishment,” in which the stress and resource drain of facing trial for trumped-up charges are intended to diminish activists’ ability to organize. The RICO case itself seeks to frame basic political activity, such as distributing food or attending a protest, as racketeering and political conspiracy.

Physical violence

| Hustle / Projection | |

| Kicks, punches, slaps | |

| Feet / knees on the nape of the neck, chest or face | |

| Blows to the victim while under control and/or on the ground | |

| Blows to the ears | |

| Strangulation / chokehold | |

| Painful armlock | |

| Fingers forced backwards | |

| Spraying with water | |

| Dog bites | |

| Hair pulling | |

| Painfully pulling by colson ties or handcuffs | |

| Sexual abuse | |

| Use of gloves | |

| Use of firearm | |

| Use of “Bean bags” (a coton sack containing tiny lead bullets) | |

| Use of FlashBall weapon | |

| Use of sound grenade | |

| Use of dispersal grenade | |

| Use of teargas grenade | |

| Use of rubber bullets weapon (LBD40 type) | |

| Use of batons | |

| Use of Pepper Spray | |

| Use of Taser gun | |

| Use of tranquillisers | |

| Disappearance |

Psychological violence

| Charge of disturbing public order | |

| Charge of rebellion | |

| Accusation of beatings to officer | |

| Charge of threatening officer | |

| Charge of insulting an officer | |

| Charge of disrespect | |

| Charge of resisting arrest | |

| Photographs, fingerprints, DNA | |

| Threat with a weapon | |

| Aggressive behaviour, disrespect, insults | |

| Charging without warning | |

| Car chase | |

| Calls to end torment remained unheeded | |

| Sexist remarks | |

| Homophobic remarks | |

| Racist comments | |

| Mental health issues | |

| Failure to assist a person in danger | |

| Harassment | |

| Arrest | |

| Violence by fellow police officers | |

| Passivity of police colleagues | |

| Lack or refusal of the police officer to identify him or herself | |

| Vexing or intimidating identity check | |

| Intimidation, blackmail, threats | |

| Intimidation or arrest of witnesses | |

| Prevented from taking photographs or from filming the scene | |

| Refusal to notify someone or to telephone | |

| Refusal to administer a breathalyzer | |

| Refusal to fasten the seatbelt during transport | |

| Refusal to file a complaint | |

| Refusal to allow medical care or medication | |

| Home search | |

| Body search | |

| Lies, cover-ups, disappearance of evidence | |

| Undress before witnesses of the opposite sex | |

| Bend down naked in front of witnesses | |

| Lack of surveillance or monitoring during detention | |

| Lack of signature in the Personal Effects Register during detention | |

| Confiscation, deterioration, destruction of personal effects | |

| Pressure to sign documents | |

| Absence of a report | |

| Detention / Custody | |

| Deprivation during detention (water, food) | |

| Inappropriate sanitary conditions during detention (temperature, hygiene, light) | |

| Complacency of doctors | |

| Kettling (corraling protestors to isolate them from the rest of the demonstration) | |

| Prolonged uncomfortable position |

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

- 2025.07.06_CrimethInc_The.Trial.Of.Ayla.King.And.The.Other.Stop.Cop.City.RICO.Cases.pdf

- 2025.07.07_Fox5_Mistrial.Declared.For.Stop.Cop.City.Activist.Ayla.King.pdf

- 2024.01.10_AP.News_Court.Again.Delays.Racketeering.Trial.Against.Activist.Accused.In.Violent.Stop.Cop.City.Protest.pdf

- 2023.03.06_FOX5_23.Charged.In.Clash.Between.Protestors.And.Police.At.Future.Atlanta.Public.Safety.Training.Center.pdf

- Lawyer :

- Collective :

- Donations: donate to the Atlanta Solidarity Fund

- List of all the fundraisers for individual Stop Cop City defendants

- Read about another Stop Cop City defendant, John “Jack” Mazurek, and donate to his support fund.

- Read about the court hearing that took place on May 14, 2025 here and here.

- Media coverage is aggregated here.

- Learn more about the J20 cases and the legal support strategy that resulted in a total victory over the mendacious and unprincipled prosecutors, start here.