July 8, 1978 – at the intersection of Carlos III Avenue and Roncesvalles Street – Pamplona

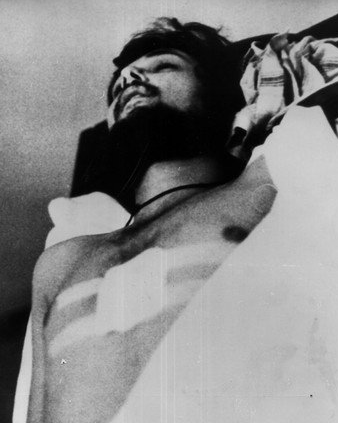

23-year-old. Shot in the head : deceased

- Last update: 15:13 - First published

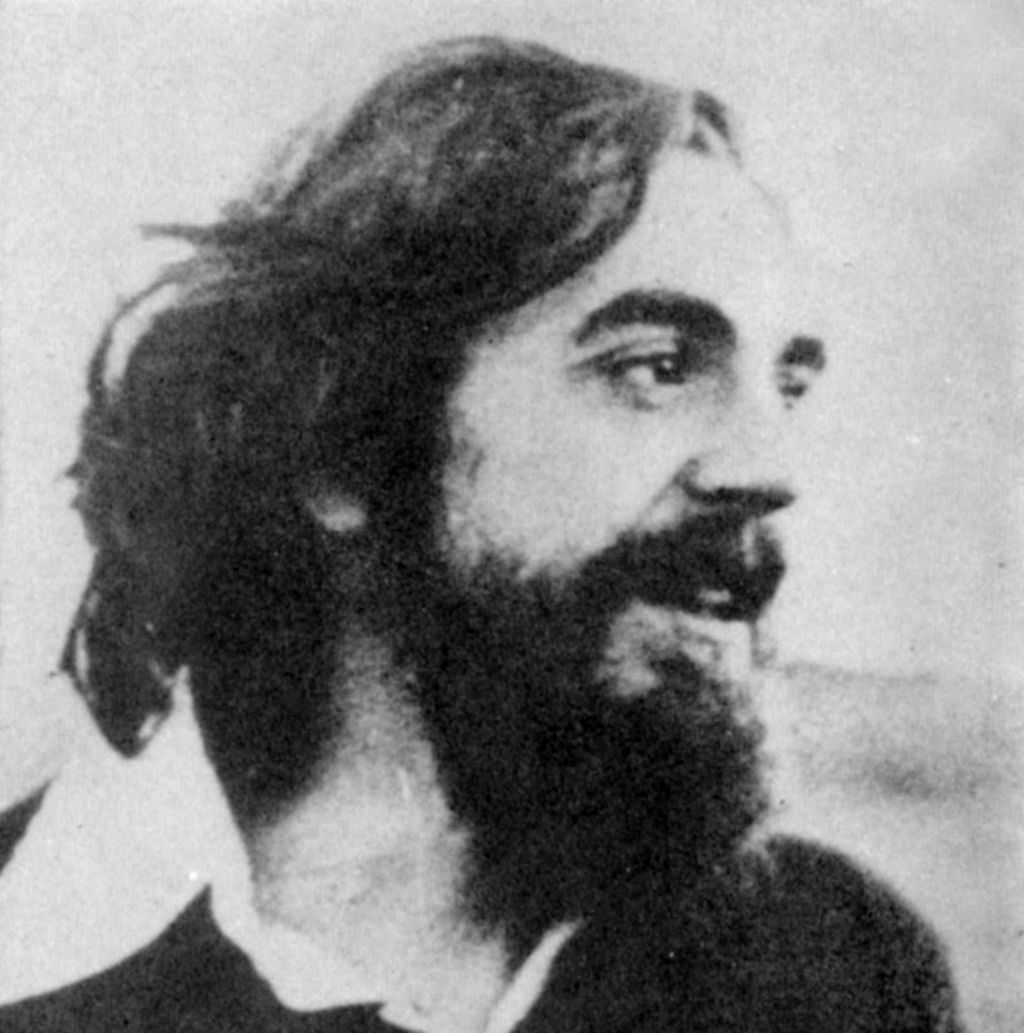

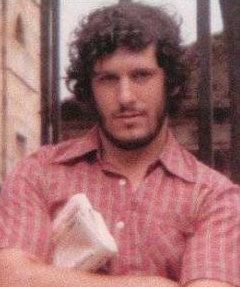

Germán Rodríguez Saiz was a militant of the radical left-wing formation LKI (Revolutionary Communist League, which emerged from ETA), killed during the 1978 Sanfermines festival by a police shot during the confrontations that took place that day between the radical left and the forces of law and order.

During 1977 and 1978 Spain was undergoing the transition from dictatorship to democracy, and the extreme left and nationalist groups opposed to the Transition were confronted by the police and extreme right-wing elements. In Pamplona these were very convulsive months (pro-amnesty week of 1977 demanding the release of political prisoners with blood crimes -the rest had been released in 1976-, occupation of the City Hall by radicals, frequent riots and attacks on the forces of law and order to force their reaction). On May 9, 1978 a device exploded, injuring four people and causing the death of another. On May 10, the murder of Civil Guard Second Lieutenant José Antonio Eseverri took place in the streets of Pamplona, with knives and kicks after having been disarmed.

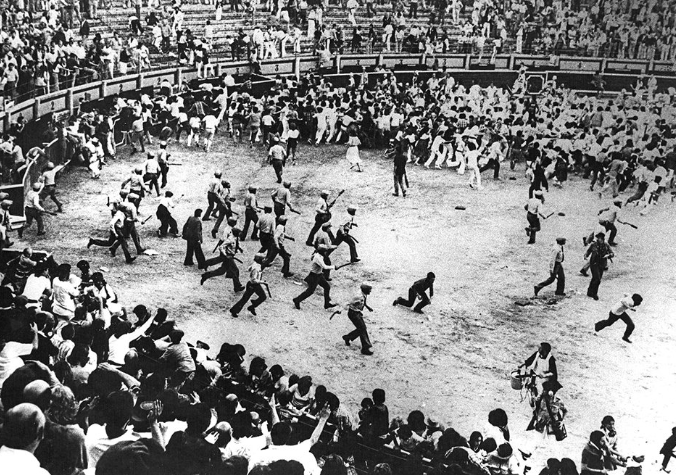

Under these circumstances, the 1978 San Fermin festivities began. On July 8, in the Pamplona Bullring, at the end of the bullfight, several peñas of Pamplona came down to the bullring with banners in favor of amnesty. This produced a confrontation (first with shouting and then with blows) with sectors of the public of opposing opinion. The Armed Police broke into the bullring.

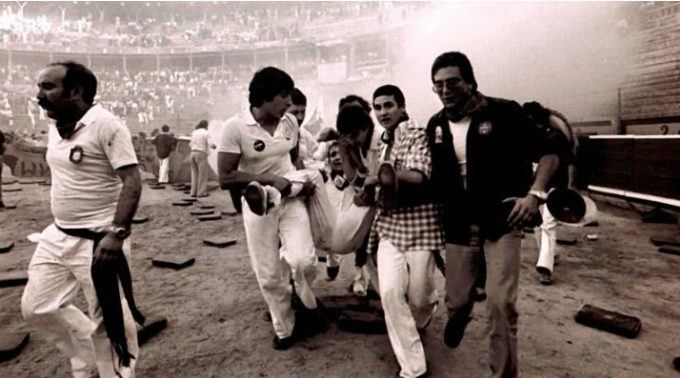

The Armed Police burst into the square and fired smoke canisters and rubber balls dispersing those present, except for a group that took refuge in the aisles and responded by throwing objects. The Armed Police in turn responded with live fire, producing 7 bullet wounds (out of a total of 55 wounded treated).

Germán died when he was shot in the head by the police at the intersection of Carlos III Avenue and Roncesvalles Street. Using the excuse that he had unfurled a banner in favor of amnesty after the bullfight, the police entered the bullring and opened fire.

“Shoot with all your energy and as hard as you can, you don’t care if you die” was recorded as they ordered. The riots spread throughout the city, and the 23-year-old man was shot dead.

The police fired about 7,000 rounds and 130 bullets during the riots, injuring 150 citizens, eleven of them seriously. No one has ever been prosecuted for the events. A crowd gathered at Rodriguez’s funeral, and Felipe Gonzalez himself was there. Protests spread throughout the Basque Country.

Physical violence

| Hustle / Projection | |

| Kicks, punches, slaps | |

| Feet / knees on the nape of the neck, chest or face | |

| Blows to the victim while under control and/or on the ground | |

| Blows to the ears | |

| Strangulation / chokehold | |

| Painful armlock | |

| Fingers forced backwards | |

| Spraying with water | |

| Dog bites | |

| Hair pulling | |

| Painfully pulling by colson ties or handcuffs | |

| Sexual abuse | |

| Use of gloves | |

| X | Use of firearm |

| Use of “Bean bags” (a coton sack containing tiny lead bullets) | |

| Use of FlashBall weapon | |

| Use of sound grenade | |

| Use of dispersal grenade | |

| Use of teargas grenade | |

| Use of rubber bullets weapon (LBD40 type) | |

| Use of batons | |

| Use of Pepper Spray | |

| Use of Taser gun | |

| Use of tranquillisers | |

| Disappearance |

Psychological violence

| Charge of disturbing public order | |

| Charge of rebellion | |

| Accusation of beatings to officer | |

| Charge of threatening officer | |

| Charge of insulting an officer | |

| Charge of disrespect | |

| Charge of resisting arrest | |

| Photographs, fingerprints, DNA | |

| Threat with a weapon | |

| Aggressive behaviour, disrespect, insults | |

| X | Charging without warning |

| Car chase | |

| Calls to end torment remained unheeded | |

| Sexist remarks | |

| Homophobic remarks | |

| Racist comments | |

| Mental health issues | |

| Failure to assist a person in danger | |

| Harassment | |

| Arrest | |

| Violence by fellow police officers | |

| Passivity of police colleagues | |

| Lack or refusal of the police officer to identify him or herself | |

| Vexing or intimidating identity check | |

| Intimidation, blackmail, threats | |

| Intimidation or arrest of witnesses | |

| Prevented from taking photographs or from filming the scene | |

| Refusal to notify someone or to telephone | |

| Refusal to administer a breathalyzer | |

| Refusal to fasten the seatbelt during transport | |

| Refusal to file a complaint | |

| Refusal to allow medical care or medication | |

| Home search | |

| Body search | |

| Lies, cover-ups, disappearance of evidence | |

| Undress before witnesses of the opposite sex | |

| Bend down naked in front of witnesses | |

| Lack of surveillance or monitoring during detention | |

| Lack of signature in the Personal Effects Register during detention | |

| Confiscation, deterioration, destruction of personal effects | |

| Pressure to sign documents | |

| Absence of a report | |

| Detention / Custody | |

| Deprivation during detention (water, food) | |

| Inappropriate sanitary conditions during detention (temperature, hygiene, light) | |

| Complacency of doctors | |

| Kettling (corraling protestors to isolate them from the rest of the demonstration) | |

| Prolonged uncomfortable position |

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

- Lawyer :

- Collective :

- Donations :