| AGRESSION DATE | VICTIM | PLACE | OUTCOME | LINK |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005.01.07 | OURY, Jalloh | Dessau | Burnt to death in a prison cell | Read |

| 2002.00.00 | BICHTERMANN, Mario | Dessau | Died from an unsupervised skull fracture | |

| 1997.00.00 | ROSE, Hans-Jürgen | Dessau | Died from internal injuries hours after being released |

[Source: Unpublished.de]

[Source: Kudoz to the brave Abdallahxbin!]

[Source: KudoZ to Ryad.Aref!]

The repressive forces attack peaceful pro-democracy protesters once again and disperse their protest calling for an end to the war of starvation and genocide.

[Sources: KudoZ Abdallahxbin!]

[Source: kudoZ Ryad Aref!]

While covering a protest in solidarity with Gaza in Berlin, a journalist was pushed by a policeman despite clearly wearing her press badge and doing her job. The images raise serious questions about press freedom in public spaces.

[Source: Ryad Aref]

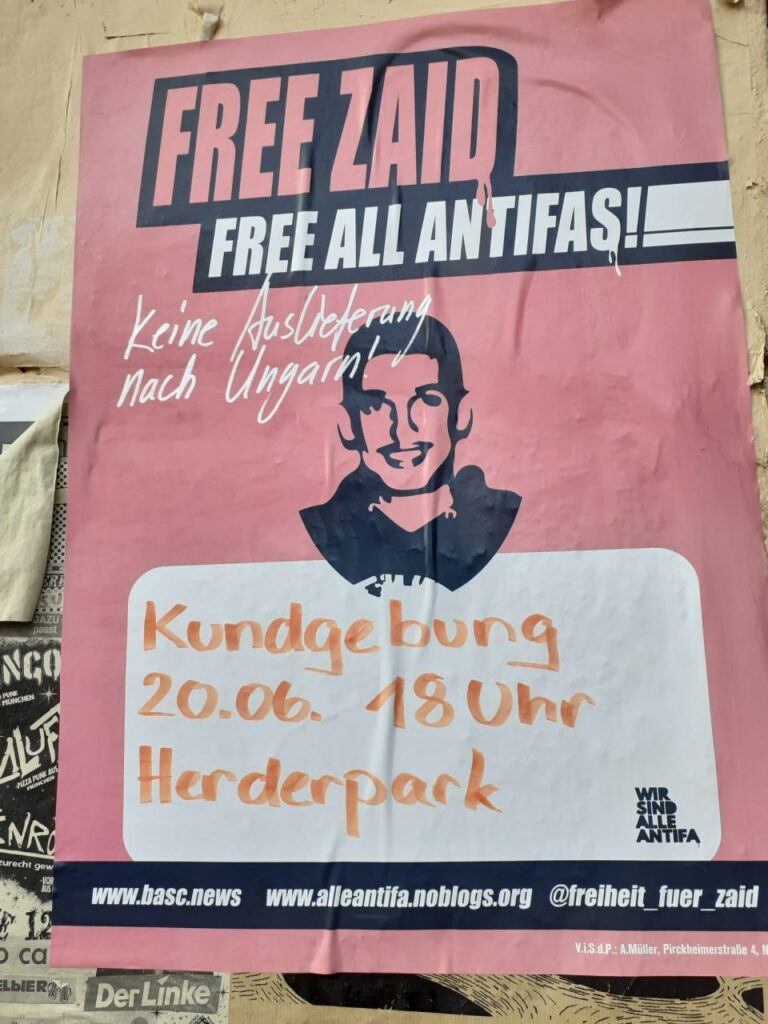

Zaid A. is a fellow Syrian citizen, resident in Germany, who was on the run after being charged for the events that took place during the Day of Honor in Budapest in 2023.

Along with other co-defendants, he had decided to turn himself in to the authorities in February 2025 and spent three months in prison. He was released on May 2nd and remains at liberty, albeit with many restrictions.

However, Hungary’s extradition request is still pending against him, and it will be determined in the coming weeks whether the Cologne court or the Federal Court in Berlin will have jurisdiction over his case.

The charges that the German court is bringing against the six German comrades who turned themselves in (Nele A., Emilie D., Paula P., Luca S., Moritz S. and Clara W.) include: membership of a criminal organisation, grievous bodily harm and attempted murder, each with varying degrees of involvement.

The Federal Prosecutor’s Office (GBA) essentially accuses them of founding a national criminal organization and, as such, of ambushing and attacking people during the “Day of Honor” in Hungary. European arrest warrants have been issued for some of these individuals. However, the GBA stated that national prosecutions take precedence over those against German citizens, and that the prosecution of Germans will therefore take place in Germany.

Zaid‘s case is different because he is a foreigner. Due to his lack of citizenship, the principle of active personality, which allows a state to criminally prosecute its own citizens, does not apply to him. Even if he could be investigated for involvement in a national criminal organization, the charges of personal injury committed against him in Hungary could not be prosecuted in Germany.

[Source: Free All Antifas]

[Source: Molotov]

A few Super 8 snippets from the fighting around Nollendorfplatz on June 11, 1982 (Anti-Reagan riots).

h/t AutonomeGeschichte @radicalpast@todon.nl